We paid one of our regular visits to Common Hill Nature Reserve on 22nd March. See here and here for January and February reports. The trees are still waiting to leaf up but the sward is greening up nicely as this view from the corner near the main North meadow shows......and looking back towards...

New Arrivals - Frogspawn

First frogspawn sighting of 2022 (23rd March) in our small garden pond......or in close-up...No sign of the parents!The appearance of frogspawn is an annual event. Unfortunately, we haven't kept past records of first sightings; anecdotally, this year seems to be later than usual.The arrival of...

Forest of Dean Sculpture Park - Taster Session

Returning from a short holiday near Chepstow, we stopped off at Tintern Abbey (raining) and Beechenhurst in the Forest of Dean (still raining). It stopped raining when we got home. Despite the rain, we enjoyed looking around Tintern Abbey (it rained last time we were there if I remember correctly) walking...

Tulip Time

.jpg)

The first fully-fledged tulip flower in the garden came out on the 17th March, or maybe a day or so earlier, along with these tulipa turkestanica ...Here's hoping for a tulip display to match last year...

Wild about Daffodils

Just over the border in Gloucestershire, in an area known as the Golden Triangle, is the best place to see wild daffodils in this part of the world. The villages of Kempley (19-20th March 2022) and Dymock (26-27th March 2022) host daffodil weekends where you can be guided or just wander freely...

,

"What is that?", I hear you ask (rhetorically). It appeared today - in the kitchen garden - during a sunny period; the sky was blue and cloudless. My 'dash' came to a full stop. I'll need my phone: a close-up photo of a comma will look great in a blog post...

First Garden Butterfly of 2022

Following on from our first butterfly of 2022, I can now report on the first 2022 butterfly to appear in the garden on March 18th......as with 2021, it was a peacock butterfly. The butterfly spent time on the paved patio, warming itself in the early spring sunshine (16 ℃ and sunny at 1410...

First Butterfly of 2022

We have just returned from a short holiday near Chepstow having passed through the Forest of Dean on our way there. One of our stops was at Cannop Ponds; two pre-1830 ponds built to supply water to a waterwheel at Parkend Ironworks. 14th March 2022 was a warm sunny day; in fact the warmest...

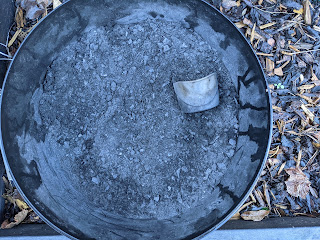

BIOCHAR(M OFFENSIVE)

I'm not sure when I got my first HOTBIN composter; I remember buying it from Tony Callaghan, inventor of the HOTBIN, before he sold the patents and company to DS Smith in January 2016. Tony then moved into biochar R&D/manufacturing with his new company SoilFixer.I bought my first lot of biochar...

View from the Rear Window - February 2022

January 2022 was warm and February continued along the same lines. See here, here, here and here. Indeed it has been a warm winter overall and, as a consequence, this wallflower has never stopped flowering over the winter months (Dec - Feb inclusive) ...Of course, the main feature of the month...

Hot Composting #1

As an avid composter, I've been meaning to write a series of articles on how I compost kitchen and garden waste in a small urban garden. I'm shocked, shocked to find my one and only post on this topic was 18 months ago!From the start, I should emphasize that I will be mainly discussing 'Hot...

Popular Posts

-

Celery and celeriac are the same plant (Apium graveolons) with the former (var. graveolons) grown for its stalks and leaves and the latt...

-

Polytunnel - 3rd August 2021 In the kitchen garden, I have a 3m x 4m polytunnel supplied and erected by Haygrove in Spring 2011; this wil...

-

Our next-but-one neighbours are on the move and asked if I could empty their plastic compost-bin. They wanted to take the bin with them but...

Blog Archive

-

►

2025

(71)

- ► April 2025 (11)

- ► March 2025 (14)

- ► February 2025 (8)

- ► January 2025 (11)

-

►

2024

(122)

- ► December 2024 (3)

- ► November 2024 (11)

- ► October 2024 (13)

- ► September 2024 (8)

- ► August 2024 (9)

- ► April 2024 (12)

- ► March 2024 (14)

- ► February 2024 (13)

- ► January 2024 (12)

-

►

2023

(137)

- ► December 2023 (11)

- ► November 2023 (10)

- ► October 2023 (8)

- ► September 2023 (7)

- ► August 2023 (9)

- ► April 2023 (17)

- ► March 2023 (15)

- ► February 2023 (12)

- ► January 2023 (17)

-

▼

2022

(138)

- ► December 2022 (7)

- ► November 2022 (13)

- ► October 2022 (14)

- ► September 2022 (10)

- ► August 2022 (14)

- ► April 2022 (13)

- ▼ March 2022 (11)

- ► February 2022 (12)

- ► January 2022 (10)

-

►

2021

(53)

- ► December 2021 (5)

- ► November 2021 (11)

- ► October 2021 (8)

- ► September 2021 (2)

- ► August 2021 (3)

- ► April 2021 (3)

- ► March 2021 (2)

- ► February 2021 (6)

- ► January 2021 (4)

-

►

2020

(22)

- ► December 2020 (3)

- ► November 2020 (2)

- ► October 2020 (1)

- ► September 2020 (1)

- ► August 2020 (1)